Illinois researchers are responding to the need for personalized medicine for cancer patients by developing a groundbreaking innovation: the Oncopig cancer model. This new platform will improve and accelerate cancer detection and treatment techniques.

The collaboration between the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, University of Illinois at Chicago, and their respective Cancer Centers was initiated by Cancer Center at Illinois member and UIUC Gutgsell Professor of animal sciences, Lawrence Schook. The team followed their mantra, “to meet the unmet clinical need,” throughout the project. Coupled with their Modeling Oncology on Demand (MOOD) technique, this model enables researchers to create a tumor in a pig that resembles and behaves just like a human tumor.

Although the team’s interests may vary at first glance—ranging from clinical to experimental—they share a common interest in advancing patient treatments and clinical outcomes. They chose to develop the Oncopig model because human clinical trials are limited and animal models help researchers identify, test, and understand new types of therapies.

“There was a convergence of basic science and clinical science that merged here,” Schook said. “We have been very fortunate that we all bring a different perspective and expertise, and it speaks to a lot of what the Cancer Center at Illinois is about. There is an unmet clinical need, and you build a team that can address it.”

Combining the Oncopig model with modern gene editing techniques such as CRISPR allows for development of genetically defined tumors that mimic human tumors at the genetic level. The high level of similarity between pigs and humans allows researchers and clinicians to develop the best treatment strategy for cancers of all types. The pig is also potentially useful for any type of therapy, including radiation, surgery, drugs, devices (due to the similar size of the pig to human patients), or even immunotherapy, since the model is immunocompetent.

Cancer is not usually an isolated incident and occurs in concert with other diseases or risk factors. The ability of the Oncopig to model both clinically relevant tumors and comorbidities fills a gap where other animal models cannot mimic the human body or provide the same wealth of information on treatment response.

“Our goal was to create something that mimics not only the tumors that a patient has but the background in which that tumor occurred so we are testing therapies in a more realistic background,” said Ron Gaba, Interventional Radiologist at UI Health.

“Another thing we are interested in is the effect of these co-morbidities on the tumors themselves,” said Kyle Schachtschneider, Research Assistant Professor in Radiology, UIC. “Tumors can arise because of the environment and we are interested in the impact of that, and how it occurs in different patient demographics like race and socioeconomic status.”

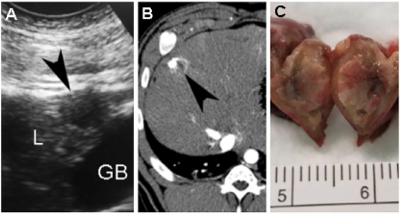

Additionally, the larger size of the pig, a cross between a minipig and a regular pig, allows for the use of clinical machines commonly used for human patients, such as clinical CT or MRI scanners. The model could be used for the development and validation of new imaging techniques, as well as discovering new early detection markers.

“The Oncopig is the most promising model to test the feasibility, efficacy, and safety of minimally-invasive procedures such as ablation and embolization, alone and in combination with selected agents, in order to improve outcomes for cancer patients across many subtypes,” said Regina Schwind, former Director of Administration of the University of Illinois Cancer Center (UIC) and current Director of Clinical Data at Tempus Labs.

The group is also exploring the implementation of the Oncopig model to study diet and its effect on tumor development, as well as expanding into different tumor types.

Written by: CCIL Communications Team

The MOOD patent has been submitted by the University of Illinois and licensed by SUS Clinicals, Inc.

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health – National Cancer Institute (1R21CA219461-01A1), National Institutes of Health – National Cancer Institute (R03 CA235109-01), and United States Department of Defense (Translational Team Science Award CA150590),