Urbana, Ill. – For decades, Katzenellenbogen has focused on understanding breast cancer and women’s health, collaborating with scientists on campus and around the world to develop better treatments and reduce morbidities from the disease. Her research has provided the framework for the development of anti-hormonal therapies used in breast cancer treatment and prevention.

“In the last 25 years, there’s been about a 40% drop in deaths from breast cancer and there have been many exciting breakthroughs and advances both in understanding breast cancer, which is a lot of what I tried to do, and also improving patient care overall,” the Swanlund Professor of Molecular and Integrative Physiology says. “In that regard, I would say we’re trying to improve both understanding of the disease and how we can reduce deaths, but also improve the quality of life for people who are on breast cancer treatments, and that means reducing toxicities of some of the treatments.”

Katzenellenbogen, alongside her husband, Swanlund Chaired Professor of Chemistry John Katzenellenbogen, has researched and developed improvements of anti-estrogens, such as the commonly-used Tamoxifen, and the second-line treatment Fulvestrant.

“There are several major subtypes of breast cancer, and the most abundant, about 70% of breast cancers, are called estrogen receptor-positive (ER-positive), meaning they contain the estrogen receptor,” Katzenellenbogen explains. “The estrogen receptor is the main factor that we and others try to target, because if you can turn off the estrogen receptor, you very effectively can suppress these cancers.”

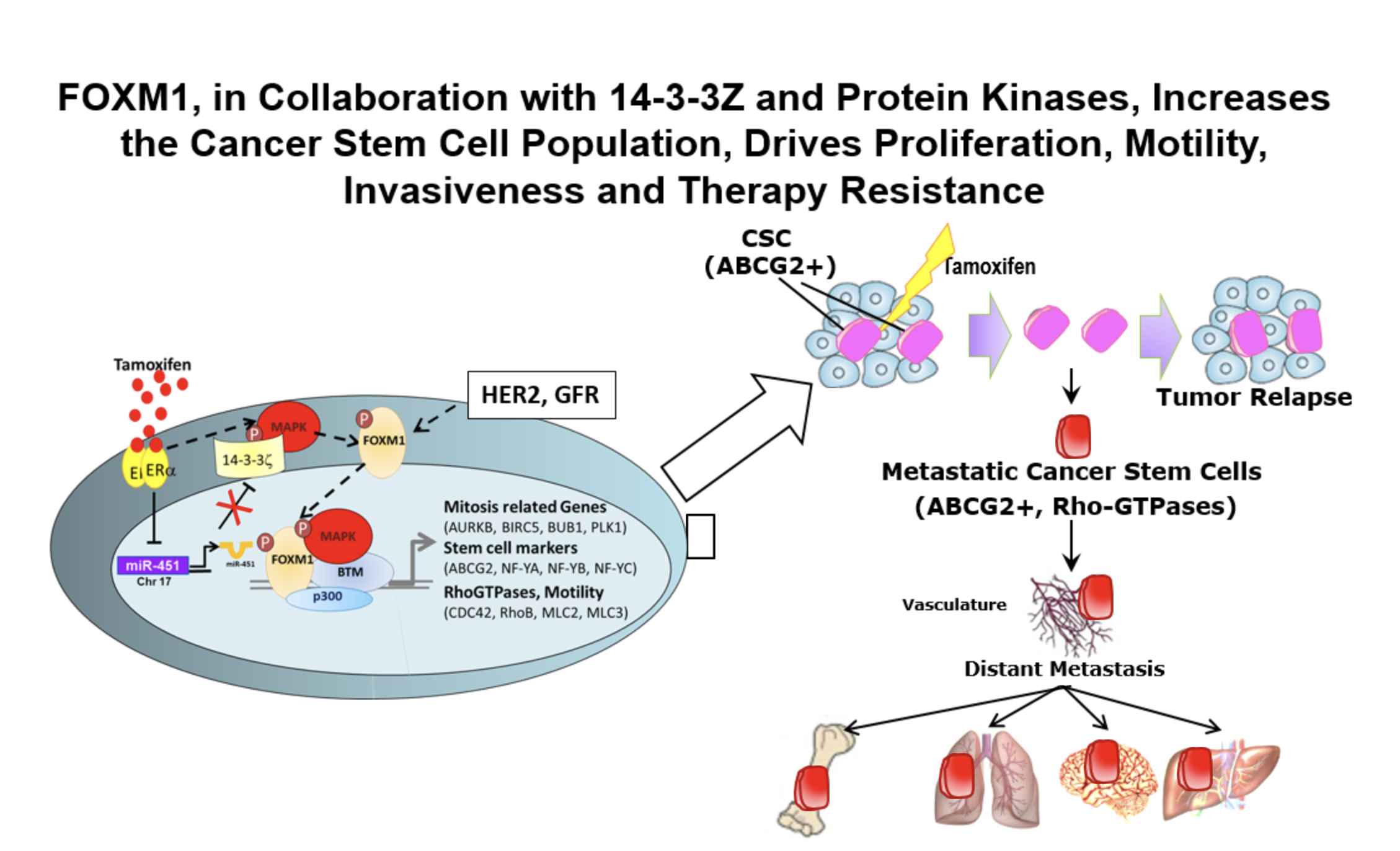

Through their work, the Katzenellenbogens’ labs determined cancers often develop resistance to antiestrogens after time, prompting a closer look at the biology of breast cancer resistance. In particular, they have researched the impact of transcription factor FOXM1 in ER-positive and in triple negative breast cancer, the latter being an aggressive subtype of the disease that lacks the estrogen receptor and frequently metastasizes. The highly upregulated FOXM1 controls many cell activities that lead to cancer progression and metastasis. Their labs found that these inhibitory compounds can suppress the progression of ER-positive and also triple negative breast cancer cells and tumors.

“Now we’re looking at combination treatments because most treatments now utilize more than one agent,” she says. “It turns out that in certain cases, having two or three compounds together that target different but related activities, sometimes in the same or interacting pathways, will allow you to more effectively treat cancer or heart disease or other kinds of medical issues at lower doses with fewer side effects.”

Their goal is to find combinations that will be effective synergistically. Katzenellenbogen says there’s also a big push right now to develop approaches and drug treatments that can be used at lower amounts, such as so-called targeted treatments, precision medicine, and personalized medicine. When biopsies are conducted or tumors are removed, they can be sent off for genome sequencing to help determine the best course of action. That means if a woman’s cancer does not have estrogen receptor, she won’t be treated with anti-hormones.

Combining inhibition of FOXM1 with current/new therapies should improve clinical outcome – in several breast cancer subtypes with high FOXM1, and possibly in other types of cancers with high FOXM1 (prostate, glioblastoma, etc.)

“There’s much more emphasis now on matching the treatments with the particular properties of the cancer of an individual patient,” Katzenellenbogen says. “That really allows for much more effective treatments.”

According to the National Institutes of Health, breast cancer is the second most common cancer in women following skin cancer. An estimated 281,550 people have been diagnosed with the disease in 2021. Nearly 13% of women will be diagnosed with breast cancer at some point during their lifetime.

“There’s no one that hasn’t had relatives or good friends who have been diagnosed with breast cancer,” Katzenellenbogen acknowledges. “Most have done very well, but I think it is still a disease that people dread.”

The 5-year relative survival rate is now 90.3%. For women whose breast cancer is discovered while it’s still localized, the 5-year survival rate is 99%.

“While I do think we are understanding cancer much better now than ever, there is so much more to do,” she says. “I think it’s an optimistic time because of our treatments and approaches… screening is much better than ever. I think that most cancers, when treated early, can be thought of as just a chronic disease or something that you survive with, and then you die of something else. So I do think that things are much better now than 50 years ago, when it was rare that people lived their whole life for 30 or more years after cancer, and that’s not uncommon now.”

Prevention strategies have increased as well. Anti-estrogens like Tamoxifen are now authorized for prevention of breast cancer in young women at high risk for the disease.

“There’s still a lot to learn, but I think that what we have learned has been interesting and important,” Katzenellenbogen concludes. “I look forward to seeing how things go.”

– Written by Jennifer Lask, School of Molecular and Cellular Biology